The Importance of Syriac

The Importance of Syriac

Fr. Armando ElKhoury

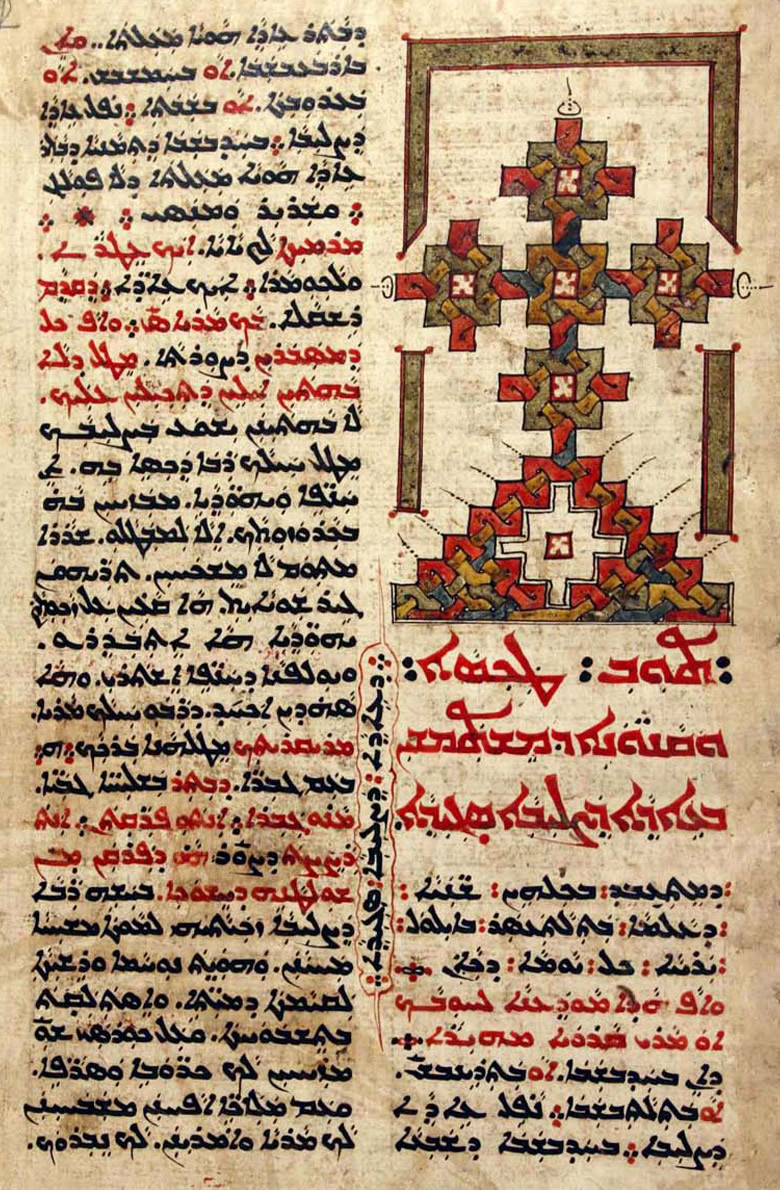

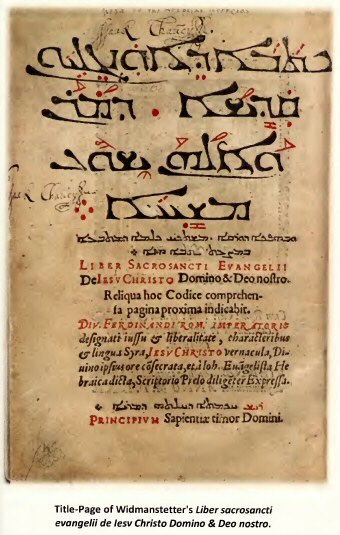

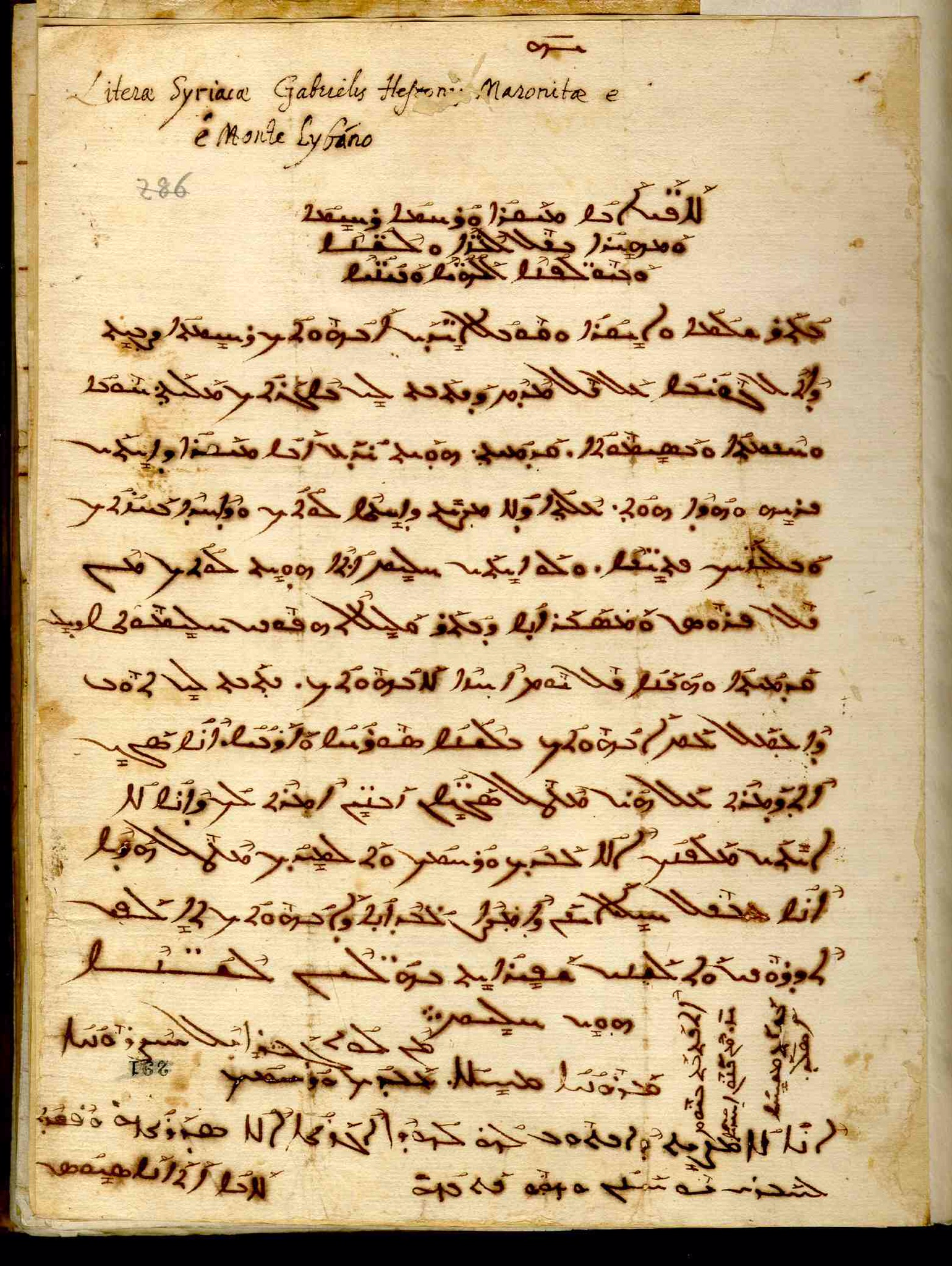

Aramaic, an ancient language spoken in the Near and Middle East, goes back to the 9th century BC. Like any language, it evolved with time and broke off into several dialects. Syriac (Suryoyo), one of these dialects that came to the scene decades after the Ascension of our Lord, became the dominant Christian literary language among the Peoples who spoke these various local Aramaic tongues and whose presence extended from the coast of present day Lebanon all the way to China.

Almost a hundred years after the coming of Islam and the Arabs’ conquests, which started in the 7th century AD, the Aramaic dialects gave way to various “Arabic” dialects. Furthermore, classical Arabic became the official language of the burgeoning Islamic empire. The Syriac speaking Peoples eventually lost their ancestral language – the language was not totally extinguished, for it continues to be spoken nowadays, albeit in a modern form – and lost, consequently, a valuable key to their rich Christian heritage.

Syriac theological giants, such as Aphrahat, the Persian Sage, Ephrem, the Harp of the Holy Spirit, and Jacob of Sarug, the Flute of the Holy Spirit, left behind spiritual, theological and liturgical treasures locked in a vast treasury whose key is the Syriac language. A tiny portion of this wealth of writings has been translated into various modern languages and is, for the most part, inaccessible to a person who is not working in this field. These spiritual ancestors are our yet to be studied Augustines and Aquinases, yet to be exhibited Rembrandts and Picasos, yet to be heard Mozarts and Wagners, yet to be read Chaucers and Shakespeares, yet to be contemplated Platos and Aristotles, and yet to be translated Hugos and Dostojefskis.

Syriac was the medium through which our unique Syriac theology was born and flourished. Therefore, it is of utmost importance for biblical studies, patristic studies, early Christianity and Syriac poetry. Moreover, it is an indispensable cultural bridge.1 To know Syriac is, therefore, to unearth the insights of our early Christian spiritual ancestors. An anonymous Syriac author wrote in the 5th century,

“I [the Church] am like the pearl

that was born under the water;

the Holy Spirit descended and drew me up

to place me on the King’s diadem.The Bridegroom alighted from His Father’s house

to prepare the wedding feast for the Bride.

In the womb of the font

did He crown and make her resplendent and pure.”“Jesus is mine and I am His.

He has desired me: He has clothed Himself in me, and I am clothed in Him.

With the kisses of His mouth has He kissed me

and brought me to His Bridal Chamber on high.”2

We, the Maronites, are not only heirs and custodians of these spiritual jewels which we share with the other Syriac Churches, but we have the responsibility to share this wealth with the world as well. What distinguishes the Antiochene Syriac Maronite Church from other Churches? It is precisely in these spiritual gold nuggets that the Maronite Church is distinguished from the other Churches. Distinguished does not, however, mean better. Rather, it allows us to recognize the uniqueness of the Maronite Church, the distinctive spiritual riches it carries and its vital role in inviting others to become members of the Body of Jesus the Messiah. A few Maronite Scholars in the United States such as Chorbishop Seely Beggiani understood this and have spent their time and energy sharing with us the Syriac theological worldview, which they cherish, through the education they acquired to instill in us a love for our Syriac tradition.

To envision a world in which all Maronites would speak Syriac, or for that matter any other language, is in my humble opinion immaterial, for that should never be within the missionary scope of the Maronite Church. Nevertheless, to envision a world with numerous Maronite scholars in Syriac studies, who would bring these hidden pearls into our hands, is significant and attainable.

Promoting Syriac studies and encouraging, fostering and supporting Maronites who might choose this field of studies is, therefore, priceless. It is not a question of remaining in the past, but rather of studying it in order to continue building our distinctive Syriac theology on the shoulders of giants. Consequently, all would have unrestricted access to this vast treasury.

1 See Sebastian Brock, “Introduction to Syriac Studies,” in Horizons in Semitic Studies, ed. John Henry Eaton, University Semitic Study Aids ; 8 (Birmingham: Dept. of Theology, Univ., 1980), 1–33. http://www.tertullian.org/rpearse/oriental/Brock_Introduction.pdf.↩

2 Sebastian Brock, “An Anonymous Hymn for Epiphany,” Parole de l’Orient, 15 (1989-1988): 175-176.↩