Maronite History

Aspects of Maronite History

by Chorbishop Seely Beggiani, STD

Adjunct Professor, Catholic University of America

The Crusades

Very little is known about the Maronites in Lebanon between the time of their being established there in the seventh and eighth centuries and the coming of the Crusades in the eleventh century. During this period the Maronites and the region were dominated by the Abbasids, whose rule was often severe and who persecuted and decimated the Maronites.

When the first Crusaders arrived in Lebanon in 1098, they were surprised and pleased to find fellow Christians who welcomed them with hospitality. We are told that the Maronites were of great assistance to the Crusaders both as guides and as a fighting force of 40,000 men known for their prowess in battle. The Franciscan F. Suriano, writing some time later, described them as “astute and prone to fighting and battling. They are good archers using the Italian style of cross-bowing.” The Crusaders not only passed through Lebanon on the way to the Holy Places, but established themselves in the country and built fortresses in a number of areas, the ruins of which remain to this day. Close relations were also established between the Latin hierarchy who accompanied the Crusaders and the Maronite Church. With the coming of the Crusaders, it would seem that the Maronites made a conscious decision to seek the support of the West. Prior to this time, the Maronites lived and thought on a provincial level. Their major concerns were to defend themselves against local heretics, a struggle based not only on a religious plane, but also on ethnic and cultural levels, and to attempt to establish a modus vivendi with Arab rulers. With the coming of the Crusaders they began to look to the West for assistance. Ties with the Holy See became closer, Western practices were adopted, and Latin influences and changes in the Maronite liturgy took place.

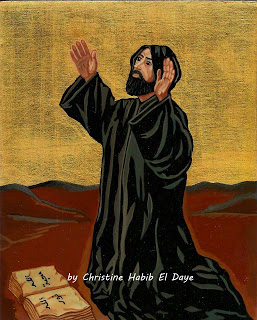

The Lebanese historian, Philip Hitti, observes: “Of all the contacts established by the Latins with the peoples of the Near East, those with the Maronites proved to be most fruitful, the most enduring. Disabilities, particularly those imposed by the Ummayyad ‘Umar, the Abbasid al-Muttawakkil, and the Fatimid al-Hakim under which the Christian minorities — at best second class citizens — lived had conditioned them for foreign influences and rendered them especially receptive to friendly approaches from Westerners.” The era of the Crusades produced a veritable renaissance in the Maronite Church. Numerous churches were built and works of religious art were produced at this time. Ernest Renan cites churches in the towns of Hattoun, Maiphouq, Helta, Toula, Bhadidat, Ma’ad, Koura, and Semar-Jebail among others as examples.

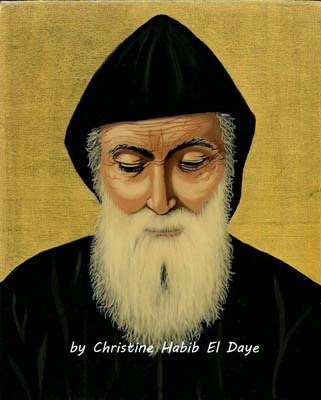

Early Latinizations

Because of their close ties with the Crusaders, the Maronites began to adopt certain Latin practices. From the 12th century they began to use bells in Lebanon, according to the way of the Western church; up to that time they had used wood for the calling to the faithful to church as the Greeks do. When Queen Constance, wife of the King of Sicily, bought the Church of the Resurrection in Jerusalem and the Sanctuary of Bethlehem, she gave to the Maronites the Grotto of the Cross and many altars in other churches in the Holy City, permitting them to celebrate on the altars of the Franks and using their religious articles. It was during this time that Maronite prelates began wearing ring, miter, and cross as the Latins do. Patriarch Jeremiah al-Amshiti was the first Patriarch to make an official visit to Rome in 1213. He assisted at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. A painting depicting a miraculous event that occurred while he celebrated the Divine Liturgy in Rome showing the consecrated Host hovering above his head was displayed in St. John Lateran for many centuries. In a Bull addressed to the Maronites in 1215, and reiterated by subsequent Popes, Pope Innocent III encouraged Latin practices, such as having the Bishop alone as the minister of Confirmation, and decreeing that nothing other than olive oil and balsam should be used in the preparation of chrism. He also called for the use of bells to discern the hours and to call the people to church. Pope Innocent also sent the Maronites church ornaments and vestments conforming to the Latin usage. Rome kept contact with the Maronites in the 13th century through visitations by Dominican and Franciscan friars. The Franciscans opened monasteries in Antioch, Tripoli, Tyre and Sidon.

The Alleged Conversion of the Maronites

If one were to consult many of the standard encyclopedias and references works regarding the history of the Maronites, the vast majority will claim that the Maronites were once heretics and experienced a conversion at the time of the Crusades in the 12th century. The Maronite Church has always denied this charge and has always affirmed its acceptance of all the teachings of the Catholic Church and its constant union with the Pope. It seems that a principal source of this false accusation was the writing of a historian of the time, William of Tyre. In his history, he speaks about a mass conversion of Maronites that took place around 1182, which involved the Patriarch, all the bishops and the laity. He identifies the heresy as that of monothelitism, the teaching that there is only one will in Christ. The heresy of monothelitism arose in the seventh century as a misguided attempt by the Emperor to bring religious peace in his empire by a formula that would seek to compromise the views of the monophysites who claimed that there was only one nature in Christ, and the Catholic party who said that there were two natures in Christ, a divine and a human one. Monothelitism taught that Christ had two natures but only one will, which in effect was the divine will. Those who advocated this heresy declared that to speak of two wills in Christ would be to say that the human will could diverge from the divine will, which would mean that Christ could sin. The Catholic party declared that to eliminate the human will in Christ would be to distort his humanity. The sixth Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 681 condemned the heresy of monothelitism.

For a church or a community of believers to be guilty of heresy, they must make the teaching a public position of their church. It must be taught by their patriarch and bishops. To be guilty of formal heresy in the Catholic Church one must be condemned officially by the Church and persist in the teaching once condemned. There is no indication that the Maronite church as a church ever taught monothelitism.

Some authors have tried to point to one or more writings of individual Maronites. But nowhere is there a false teaching attributed to a Maronite Patriarch or Bishop. Furthermore, the Council of Constantinople in condemning monothelitism listed by name those who had spread this heresy. The Maronite church is not mentioned and there is no Maronite name on the list. Regarding the claims of William of Tyre of a miraculous conversion of the Maronites, some Maronite scholars have speculated that the event might have been in actuality a public profession of faith rather than an abjuration of heresy.

Through the years opponents of the Maronites have repeated the charge of heresy for their own purposes. It is unfortunate that various encyclopedias have perpetuated this unsubstantiated charge, and not consulted the officials of the Maronite church. On the other hand, for the last nine hundred years the Popes in official declarations have consistently praised the Maronites for their perpetual union with the Church of Rome.

The Defeat of the Crusaders

Towards the end of the 13th century the Mamelukes of Egypt began to gain the upper hand in the eastern Mediterranean. The Crusaders in retreat found refuge among the Maronites in Lebanon. While the Franks tried to hold the line there, they were defeated by the Sultan’s troops. In 1267 upper Lebanon was destroyed. Many captives were beheaded, the trees were cut, and the churches destroyed. From 1289 to 1291 the whole of the Lebanese coast fell to the invaders. The once flourishing cities of the Mediterranean went up in flames as the Moslems took their vengeance on the Christians. According to

the historian Theodore of Hama, even in Kisrawan ‘not a monastery, church, or fort was saved from destruction.’ The last Crusader fortress, St. John of Acre, fell shortly after Beyrouth in 1291. A good number of Maronites grouped around their Patriarch and established at Hadeth a center of resistance. But the Patriarch himself was soon captured.

The loss of the Latin states caused the conquered to look to the island of Cyprus, acquired in 1192 by Guy de Lusignan. Many Maronites followed the movement of immigration to Cyprus. They chose to live in the higher elevations of the island where they preserved their culture and their customs. We know that there was a Maronite bishop in Cyprus as early as 1340. The Maronite immigration also extended to Rhodes. The period of the Crusades marks an important milestone in the history of the Maronites. The communications with the West from this time on were to increase and become solidified. Many religious orders were to come to Lebanon in succeeding centuries and establish institutions and schools. European culture would also be transmitted. Latinization of the Maronite rite, which had its beginnings with the Crusades, was to continue in a haphazard and uneven manner until it was formalized with the Synod of Mount Lebanon in 1736. Even politically, the Maronites looked for aid and support more often than not from the countries of Europe, especially France.